What Is Traditional Day of the Dead Art Called

For generations the Mean solar day of the Dead has been a unique and sacred festivity for people of Mexican descent on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border. El día de los Muertos, an ancient Mexican commemoration in which families reconnect with departed ancestors, provides a special opportunity to recall and celebrate the life and legacy of those who have moved ahead into the sacred lands of Mictlan, the realm of the "fleshless."

For generations the Mean solar day of the Dead has been a unique and sacred festivity for people of Mexican descent on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border. El día de los Muertos, an ancient Mexican commemoration in which families reconnect with departed ancestors, provides a special opportunity to recall and celebrate the life and legacy of those who have moved ahead into the sacred lands of Mictlan, the realm of the "fleshless."

ANCIENT Mexico

The veneration of ancestors in ritualized practices is as ancient in Mesoamerica and other areas in the Western hemisphere every bit the domestication of corn and the evolution of agriculture.

Funerary practices across Mesoamerica strongly connected departed ancestors with the life cycle in agronomics and the seasonal calendar. Ancient civilizations across present-day Mexico and Central America performed burial rituals centered on the concepts of renewal and regeneration. Through elaborate rituals to the ancestors, ancient Mexican communities and families reconnected with departed ancestors to recall and celebrate the life and legacy of those who have moved alee into the sacred lands of Mictlán.

Mictlán, co-ordinate to Ancient Mexican traditions, is conceived to be in a fluid human relationship with the globe of the "flesh" or the living. "The fleshless ones" are considered to be a living presence in this world while the "living ones" contemplate death as the natural progression of life and renewal. Ancient cities like Teotihuacan, Palenque, Chichen Itzá, Monte Albán, Mitla, Tajín, Tikal or Tenochtítlan, provide aplenty examples of the relevance of celebration of ancestors and the expressionless.

In Mesoamerican calendars (with eighteen months of xx days each) two complete months were dedicated to the departed ancestors (approximately the last week of July and the month of August in the Gregorian calendar). The Aztecs in Fundamental Mexico named these months Miccailhuitontli and Hueymiccahuitl, and for forty days they venerated ancestors and the Mictlantecuhtli, the Lord of Mictlán.

Mictlán (in Nahuatl) is often translated as "the underworld" or "the land of the dead". While some European religious writers erroneously translated it every bit "Hell," Mictlán was considered the "Great Cavern" or the "Great Womb" where living animals, humans, plants and cultures were originated and destined to rest. The bones of ancestors were commonly cached in the cornfield or in the center of the residence, correct under the antechamber. Their bones were considered essential to reactivate the life cycle in the country, especially the harvest of corn. As people were considered to be created and made of corn, they were also considered corn seed to feed the land. The veneration to the ancestor, thus, coincided with the harvest of corn across the Mesoamerican mural. The traditional ways were altered by the changing power structures that came with the Spanish Conquest and the Christianization of the region. The honoring of ancestors was moved from the 2 month celebration in July and August to coincide with Catholic All Saints Day and All Soul's Day on Nov ane and second respectively. The celebration became Dia de los Muertos.

Mictlán (in Nahuatl) is often translated as "the underworld" or "the land of the dead". While some European religious writers erroneously translated it every bit "Hell," Mictlán was considered the "Great Cavern" or the "Great Womb" where living animals, humans, plants and cultures were originated and destined to rest. The bones of ancestors were commonly cached in the cornfield or in the center of the residence, correct under the antechamber. Their bones were considered essential to reactivate the life cycle in the country, especially the harvest of corn. As people were considered to be created and made of corn, they were also considered corn seed to feed the land. The veneration to the ancestor, thus, coincided with the harvest of corn across the Mesoamerican mural. The traditional ways were altered by the changing power structures that came with the Spanish Conquest and the Christianization of the region. The honoring of ancestors was moved from the 2 month celebration in July and August to coincide with Catholic All Saints Day and All Soul's Day on Nov ane and second respectively. The celebration became Dia de los Muertos.

With the colonial influences, the departed were no longer buried in the home or the cornfield merely in churchyard burial grounds. If a family unit had money or influence, their departed could be buried under the anteroom of the church. Mexicans began to honor their expressionless in a syncretic fashion, combining Cosmic and indigenous traditions. Day of the Dead ofrendas were fix in the home and by the tombs of the departed.

With the colonial influences, the departed were no longer buried in the home or the cornfield merely in churchyard burial grounds. If a family unit had money or influence, their departed could be buried under the anteroom of the church. Mexicans began to honor their expressionless in a syncretic fashion, combining Cosmic and indigenous traditions. Day of the Dead ofrendas were fix in the home and by the tombs of the departed.

DIA DE MUERTOS AND THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION

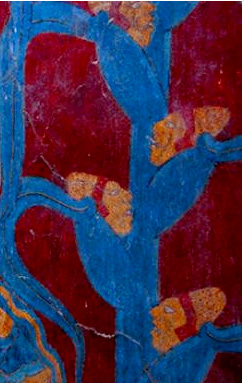

The Mexican Revolution generated a cultural renaissance for the country's ethnic roots, a new appreciation for cultural rituals in the working classes and a repositioning in visual arts away from European standards in search for the Mexican identity across time. In 1921 Diego Rivera returned to United mexican states after years in Spain and France, to lead the Mexican Muralist move, already started in public schools and government buildings. One of the commissions was at the Public Education Ministry in Mexico Metropolis in 1923. Rivera envisioned 3 big segments dedicated to popular festivities in Mexico, one of which was the Day of the Dead. Rivera'due south frescoes set the trend for the incorporation of the Día de Muertos into the visual arts.

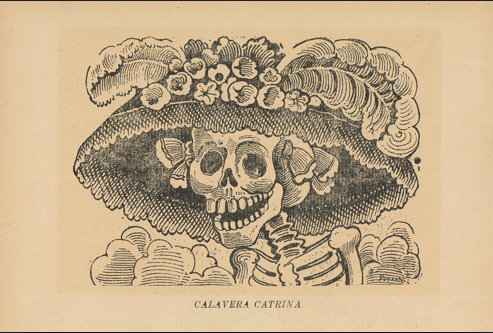

In 1930 Rivera and Frances Toor published a monograph on José Guadalupe Posada, with hundreds of his engravings, reintroducing the until-then unappreciated cartoons as artistic works. Posada's most renown engraving "La Calavera Catrina"(1910-xiii) or just "La Catrina" became the quintessential iconic personification for La Muerte and the Twenty-four hours of the Dead in Mexican culture.

Posada'due south images complemented "Calaveras" or skull poems, which poke fun at people who are alive equally if they were dead. The people beingness satirized occupied positions of ability such as politicians, public figures and the upper classes during the reign of Porfirio Díaz. The skull poems fabricated fun of the rich and powerful through irony and sense of humor; they pointed out that decease is the ultimate blaster, that we all end upwards in the aforementioned identify in the cease. "La Catrina" in particular was making fun of the excesses and arrogance of the rich aristocracy.

Every bit a immature boys, Mexican muralists Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco were very attracted to Posada's work. Rivera recounted that would visit Posada's engraving shop and listen to the engraver's words of political criticism during the stormy years leading up to the Mexican Revolution. Both Rivera and Orozco were influenced past the Posada's political tone in their artistic works.

The popularity of Posada'south works influenced artists and artisans all over Mexico. The Mean solar day of the Dead markets set up 1 week before the holiday are filled with humorous skeleton figures – bride and grooms, musicians, cowboys, drunkards, priests, etc.

CONTEMPORARY Mexico

La Catrina goes to murals, galleries and universities

In 1948 Diego Rivera featured "La Catrina" as the central effigy in his mural "Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda" in the Del Prado Hotel in Mexico Metropolis. A year before Frances Toor had published in New York "A Treasury of Mexican Folkways" with illustrations by Carlos Mérida, including the ethnographic descriptions of Day of the Expressionless celebrations in urban and rural Mexico.  Toor described it as "a national holiday" and related her observations in the Dolores Cemetery, Mitla, Oxchuc and Chan Kom, in Mexico City, Oaxaca, Chiapas and Yucatan, respectively. She finished with a report on the festivity in Janitzio, a Tarascan island in Michoacan. Toor described it every bit "the most exotic and beautiful of the ceremonies". In the 1950s the Day of the Dead became a cardinal feature for scholars and artists in Mexico searching for the sources of Mexican cultural identities in juxtaposition with the increasing modernization trends of Mexican economy and social life. Octavio Paz published in 1950 "El Laberinto de la Soledad", a collection of essays on Mexican culture in which the connections betwixt Mexicans and Expressionless were prominently featured.

Toor described it as "a national holiday" and related her observations in the Dolores Cemetery, Mitla, Oxchuc and Chan Kom, in Mexico City, Oaxaca, Chiapas and Yucatan, respectively. She finished with a report on the festivity in Janitzio, a Tarascan island in Michoacan. Toor described it every bit "the most exotic and beautiful of the ceremonies". In the 1950s the Day of the Dead became a cardinal feature for scholars and artists in Mexico searching for the sources of Mexican cultural identities in juxtaposition with the increasing modernization trends of Mexican economy and social life. Octavio Paz published in 1950 "El Laberinto de la Soledad", a collection of essays on Mexican culture in which the connections betwixt Mexicans and Expressionless were prominently featured.

DOLORES OLMEDO

A pivotal development in the expansion of the celebration into museums, galleries and public spaces occurred in connectedness with Dolores Olmedo and Diego Rivera's terminal days. Dolores Olmedo, a multitalented creative person, business woman and art collector, had modeled for Rivera in the 1920s. In 1954 Olmedo and Rivera reignited their friendship and travelled with a group to Day of the Dead commemoration in Janitzio. Olmedo collected artwork from Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and other artists, while amassing an impressive collection of Mesoamerican art besides. One year later Frida Kahlo'south dead in 1954, Diego Rivera set up a trust to create a museum in their two residences, the Casa Azul and the Anahuacalli. Rivera donated his artwork to the Mexican people under the guardianship of Olmedo. Rivera travelled in 1955 to the Soviet Union, looking for effective cancer treatment, and returned to Mexico in 1956 to reside in Acapulco. As Rivera's fight against cancer waned, Olmedo decided to create a Solar day of the Dead chantry dedicated to him, giving birth to the start public ofrenda in the history of the celebration. In 1957 Rivera returned to Mexico Metropolis and died. Dolores Olmedo decided to build artistic ofrendas every year in the Anahuacalli museum, defended to the retentivity of Diego Rivera. In partnership with the Banco de Mexico, Dolores Olmedo supervised and financed the completion of the Anahuacalli museum, which opened to the public in 1964. (The Casa Azul had become a museum in 1958.) Dolores Olmedo altars from 1956 on are therefore the first public ofrendas in Mexico that explored new ways to contain the traditional celebration into the world of contemporary art.

VISUAL ARTS

Photographers, painters, filmmakers and artists explored the Solar day of the Expressionless celebrations in Mexico extensively in the 2d one-half of the Twentieth century. Mexican photographers presented the banquet in dissimilar means, from journalistic photo-essays to more than conceptual interpretations. Nacho López visited Janitzio in 1950 to create "Noche de Muertos", documenting the festivity in the isle'south cemetery in Michoacán. Julio Mayo in 1954 and 1957, Faustino Mayo in 1955, the Casasolas in 1956, connected with this practice.

Diego Rivera used Twenty-four hour period of the Dead imagery in his murals both to highlight Mexican traditional practices as well every bit to communicate a Mexican way of looking at the nature of life itself. Frida Kahlo'due south famous painting "The Dream (The Bed)" with an image of her skeleton lying on meridian of her canopy bed over her ailing body reveals a particularly Mexican relationship with expiry, that it hovers over y'all and whispers in your ear. Equally this attitude in omnipresent in the culture, many Mexican and Chicano painters feature the skeleton in their works.

MEXICAN CINEMA

Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein traveled to United mexican states in 1930, financed by Upton Sinclair and the "Mexican Trust Moving picture" to brand a picture show about Mexicos history and people. The epilogue in the plan was defended to the Día de los muertos. Eisenstein and the company entered a dispute that ended the projection after shooting over 30 hours of movie. Without Eisenstein the company edited and released segments of the master project, "Death 24-hour interval", which was released in 1934 equally a short film. Grigory Alexandrov, Eisenstein's assistant, edited the entire film, released in 1979 every bit "Que Viva México", Eisenstein's original title. Following the steps of "Que viva Mexico" Mexican cinema used the 24-hour interval of the Dead frequently equally a resources to provide "actuality" and flavor to the delineation of working classes and ethnic groups in pop films. The immensely pop trilogy "We los pobres" (1948), "Ustedes los ricos" (1948) and "Pepe el Toro"(1953) starts and ends with the main protagonists visiting the cemetery on November 2 in Mexico City.

In 1957, American designers Charles and Ray Eames fabricated a documentary motion-picture show "Day of the Dead". Financed past the Museum of International Folk Fine art in Santa Fe, New United mexican states, "Day of the Dead" was shot in collaboration with the Museo Nacional de Artes due east Industrias Populares and researcher-photographers Deborah Sussman, Susan Girard and Alexander Girard. A fourteen-minute short documentary, "Twenty-four hour period of the Dead" provided a unique perspective on the fabric culture and popular arts embedded in the celebration.

Following the aesthetics of traditional arts: sugar-skull making, mask pattern and food preparation, the Eames featured the artful elements central to the pop tradition. In a nonetheless unparalleled fashion, the 1957 "Day of the Expressionless" reclaimed the festivity as an fine art consequence. The 1960 flick "Macario" directed by Roberto Gabaldón constitutes the first commercial motility pic centered on the Day of the Dead. Based on a short story by B.Traven published in German in 1950 (English 1953). "Macario" became an international success, earning an Oscar nomination for best foreign picture show (actually the commencement Mexican film ever to be nominated in that category) and a screening at the 1961 Cannes International Picture Festival.

CHICANO DAY OF THE Dead

In the United States, Mexican communities have turned El día de los Muertos into a public celebration of Latin@/o cultures, a ritual of rebellion & hope and an opportunity to raise awareness of cultural and historical collective memory. In the midst of the Chicano ceremonious rights move demands for political representation, access to education, labor rights for farmworkers, gender equality and anti-Vietnam War, Mexican communities in the United States also experienced a cultural revival vindicating Mexican pop traditions and celebrating the resilience of ethnic civilisation. The revival of Mexican civilisation provided new opportunities to arrange, change and transform the traditions themselves. Chicano artists, activists and intellectuals embraced the Day of the Dead with new perspectives and transformed the event into rituals of cultural affirmation, community development and artistic expression. In San Francisco and East Los Angeles two community organizations were at the forefront of this new wave: La Galería de La Raza and Cocky Help Graphics. In 1972 both groups separately organized the Día de los Muertos celebration with processions, artwork, educational and community activities. Through public rituals that merge artistic expression with community celebration, the Day of the Expressionless in California and other Chicano communities evolved into a celebration of the Mexican experience in the U.s.a.. At the core of this metamorphosis was the contribution of visual artists centering their piece of work and performances on the history and culture of Mexicans in the United States. Dia de Muertos became a vehicle for social change through the programming of multiple educational, cultural and artistic activities in the communities. Following on Olmedo and other artists work, California Chicanos turned ofrendas into conceptual artifacts that reflected on the multiple layers of the Chicano experiences. Solar day of the Dead Altars evolved from domestic family mementos into individual and collective artistic expressions. Visual artists like Ralph Maradiaga, Patsy Valdes, René Yáñez, Amalia Mesa-Bains, Ester Hernández, Gronk and many other led this new wave turning the Day of the Expressionless into a medium for creative expression, where conceptual ofrendas or artistic altars were no longer attached to family ties but embedded into contemporary trends in the arts and centered on the chicana/o experiences as a commonage entity. In 1978 the Galería de la Raza organized a path-breaking celebration, dedicating the event to Frida Kahlo, focusing on the legacy of the Mexican painter. The following decade museums, galleries and universities echoed this new trend in which the Día de los Muertos would prefer a multilayered dimension with artistic, political and cultural features. Institutions in cities similar Chicago, Detroit, San Antonio and New York began scheduling artistic events and allocating exhibition spaces to the Day of the Expressionless. The Detroit Institute of Arts, for instance, organized such an event in 1986, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Detroit Industry Murals past Diego Rivera. Excerpts from Juan Javier Pescador's forthcoming book on the history of the Day of the Dead

OFRENDAS

In preparing for the Twenty-four hours of the Dead, many families make clean and decorate the tombs of their ancestors. They use marigold flowers and candles and bring their ancestors special foods and drinks. The family sits vigil to district with their expressionless relatives. Many families set ofrendas in the home for Dia de Muertos, inviting the expressionless to the domestic space, which was a natural inclination in pre-Hispanic United mexican states, since it was common practice to bury the dead under the flooring of one's firm. If a family had money, they would bury the dead under the floor of the village chapel or in the churchyard cemetery.

Source: https://pescadorarteofrendas.wordpress.com/history/

0 Response to "What Is Traditional Day of the Dead Art Called"

Post a Comment